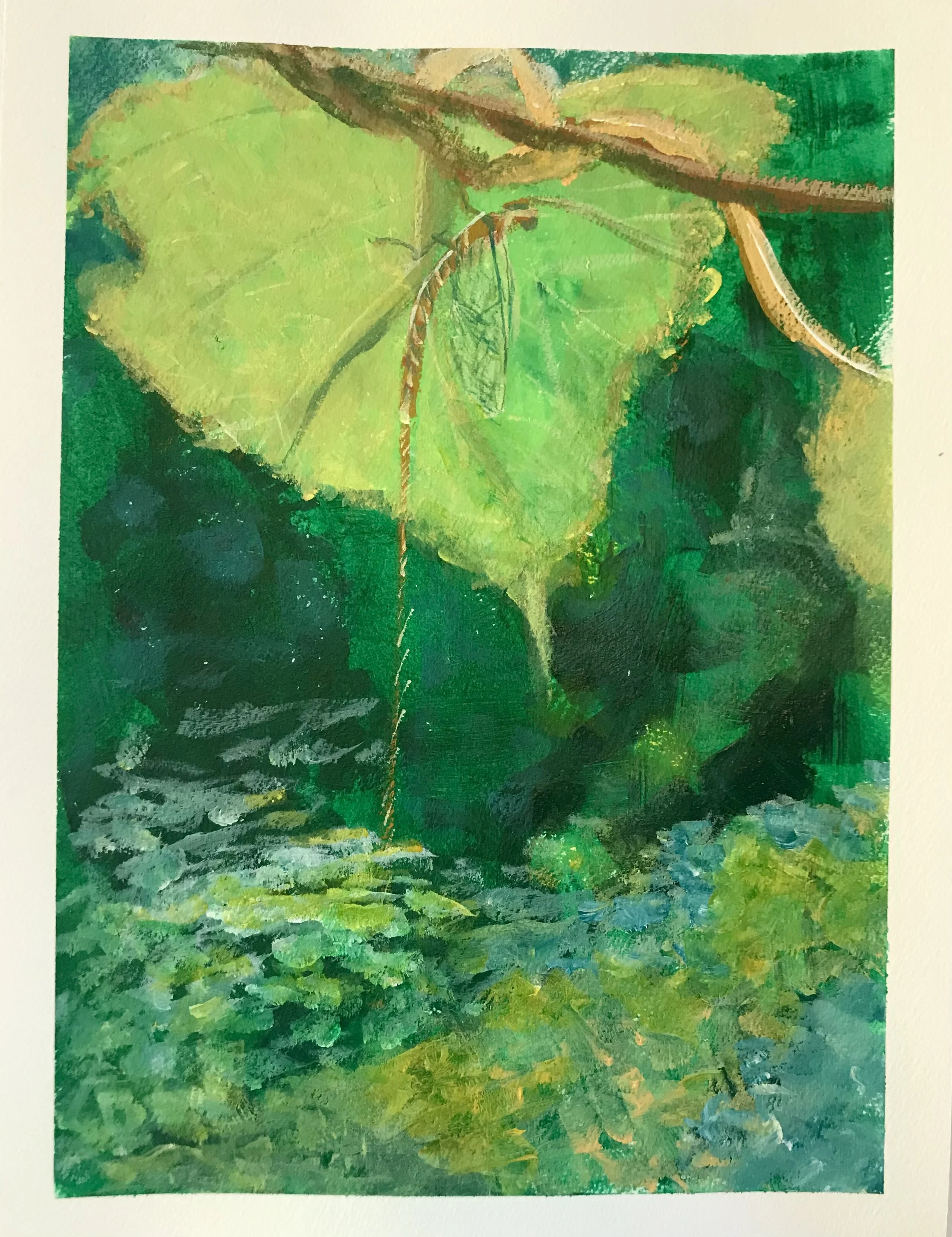

Earth is my mother, the cause of my being here.

Lac des Îles

What do I mean when I say I am from here?

My project “the earth is my mother too” was conceived to help me understand my identities of being both ‘from here’ and being ‘from another land and culture’. It took me so long to understand that for each of my ancestors on my father’s side who were born elsewhere, there is also a grandmother who was ‘from here’. The earth is my mother too, I come from the blood and bones raised from her ground.

In the frightening moments of my childhood, the land around my grandmother’s cottage was the mother who held me close. I would creep into the moss, snuffling the softness and hoping to avoid the slugs, or I would run up the footpath to the lookout and sit on the very edge of a great smooth half buried boulder, or I would circumnavigate the lake barefooted to find out if I could (I had to turn back because the shoots in the muck were so sharp). Gently the earth showed me my limits, without force or anger, she showed me what is real.

I followed my genetic pedigree as far as I could go, trying to find the first Scott who came here who I could claim as a grandfather. I lost the thread almost immediately, as my father, being born out of wedlock, never knew his father and was raised by his grandfather. When I asked about my great-grandfather’s story, I was told that Fred left his home on a farm in Ontario when he was only ten years old. He traveled alone to Montreal, intent on working on the docks, but was too small to do the heavy work needed. He was taken in by a family and apprenticed to the head of the household, and became a steamfitter. I sat with this dead-end, my great-grandfather, born without a birth certificate, finding his (mis)fortune so young. Then I turned toward my great-grandmother. My grandmother had told me about her. I learned to cook to be like her, because my grandmother would always say “oh I could never make a pie/bread/stew like my mother did”. My great-grandmother Martha could speak gaelic, and her mother was country-born, but that wasn’t something people talked about. “We” have cousins, so many, near Baie des Chaleurs, but I never met them, and now they have had families and passed away as my grandmother has, and those possible connections are lost to me.

I was brought to “the house up north” (as we liked to joke), as soon as I was born. My mother’s family traveled here to meet me. When my parents separated, I came to the house with my father and grandmother every weekend possible and all summer long (when I wasn’t traveling to the other side of my life). This was the place where I was completely free and unencumbered, I was simply myself. The ritual of arriving is so ordinary I never knew it was sacred, until it was gone. We would drive up at night, or in the dark, not to waste a single second of the weekend, and on the way my father would stop at the butcher’s to buy a steak. We parked the car on the dirt road on the hill behind the house, and my dad would go to the woodshed, exclaiming every time “why didn’t anybody leave some cut wood!”, then gathered large logs and an ax. My job was to get the kindling, twigs and dry grasses and birch bark, while he chopped our firewood. Eventually, we would enter the house and fix up the fire, and then cook the meat. The rest of the weekend we ate what he fished. I would fall asleep on the floor as close to the fire as possible, no one needed to tell me to be careful.

The House Up North